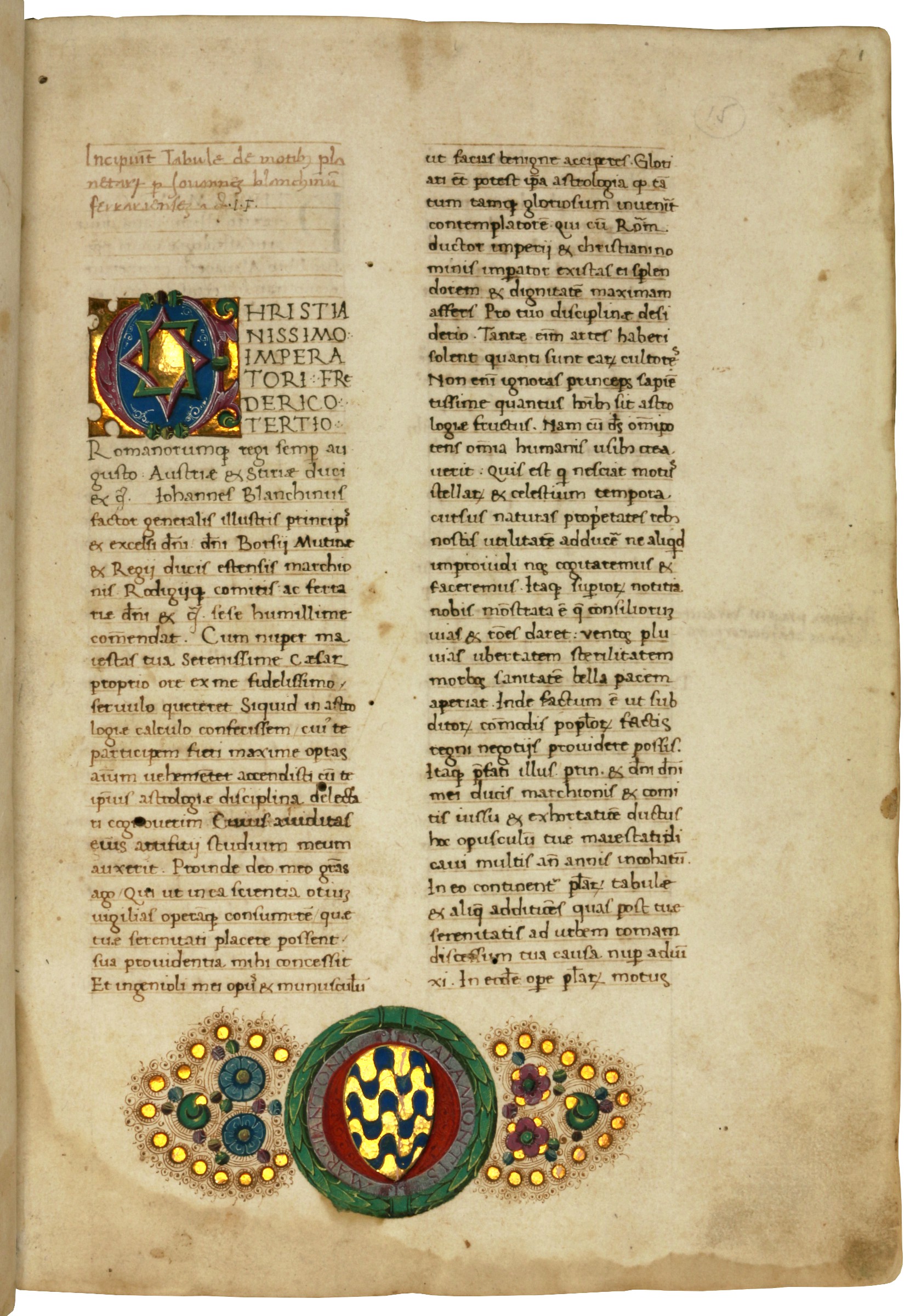

Tabulae de motibus planetarum.Ferrara, ca. 1475.

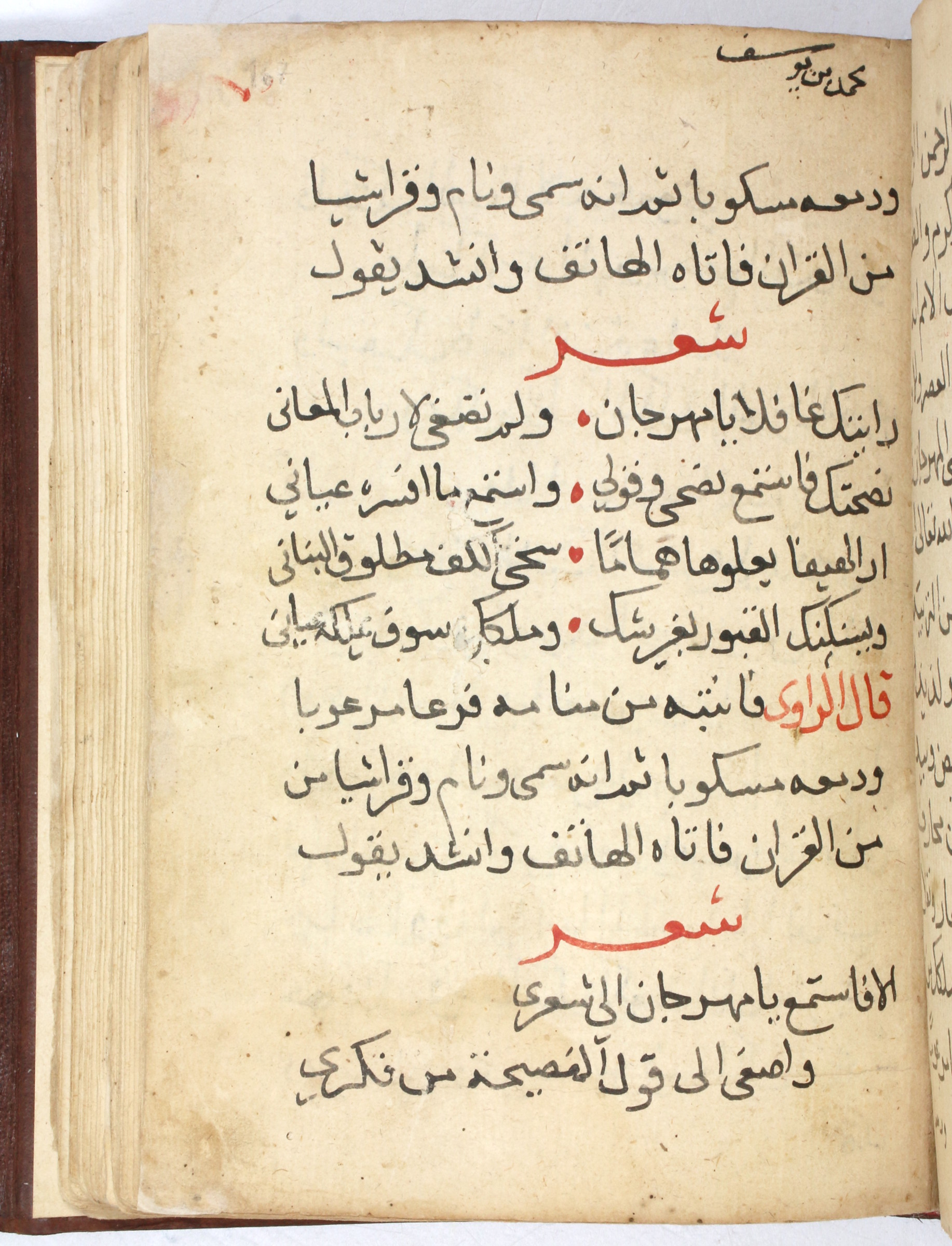

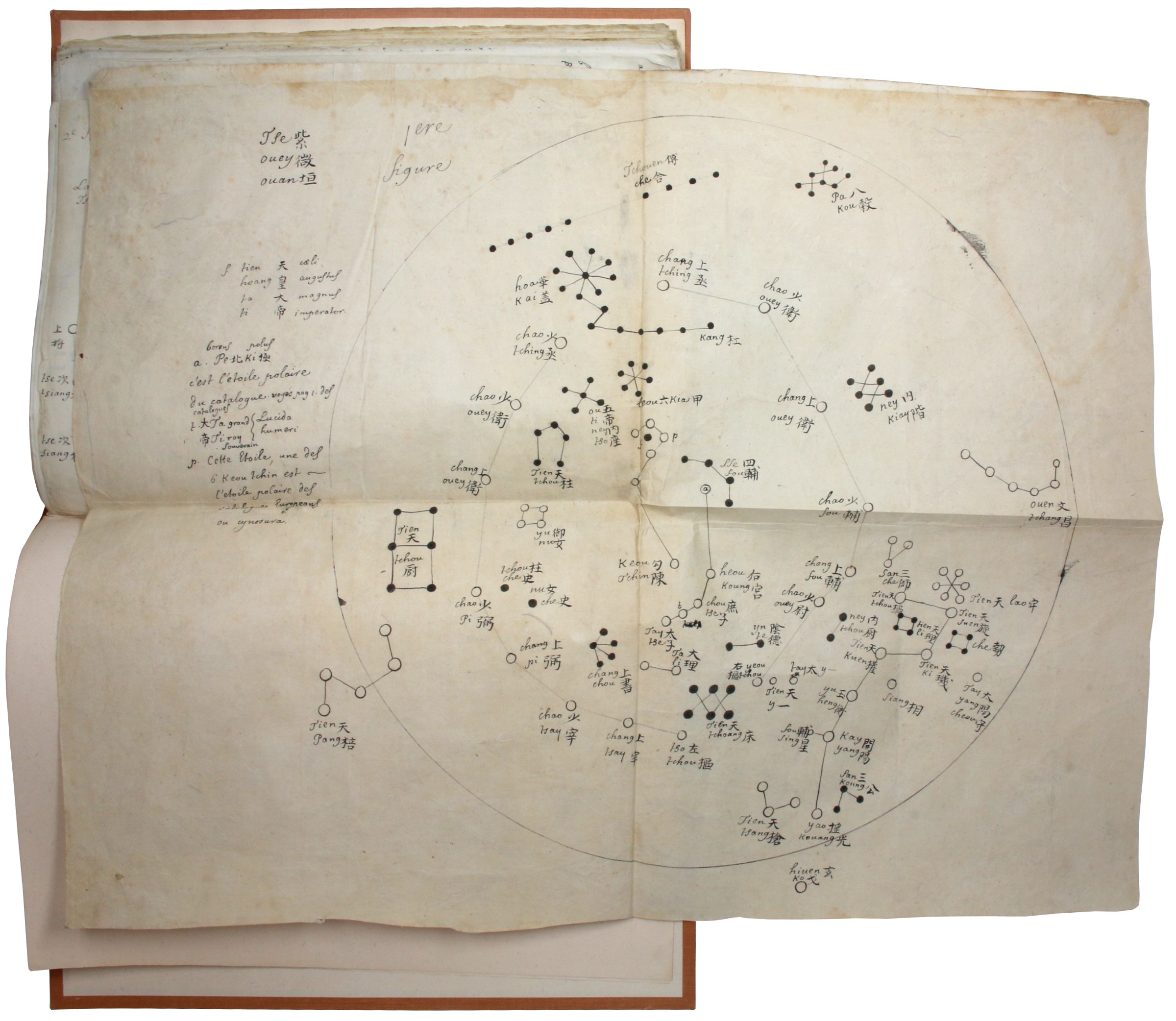

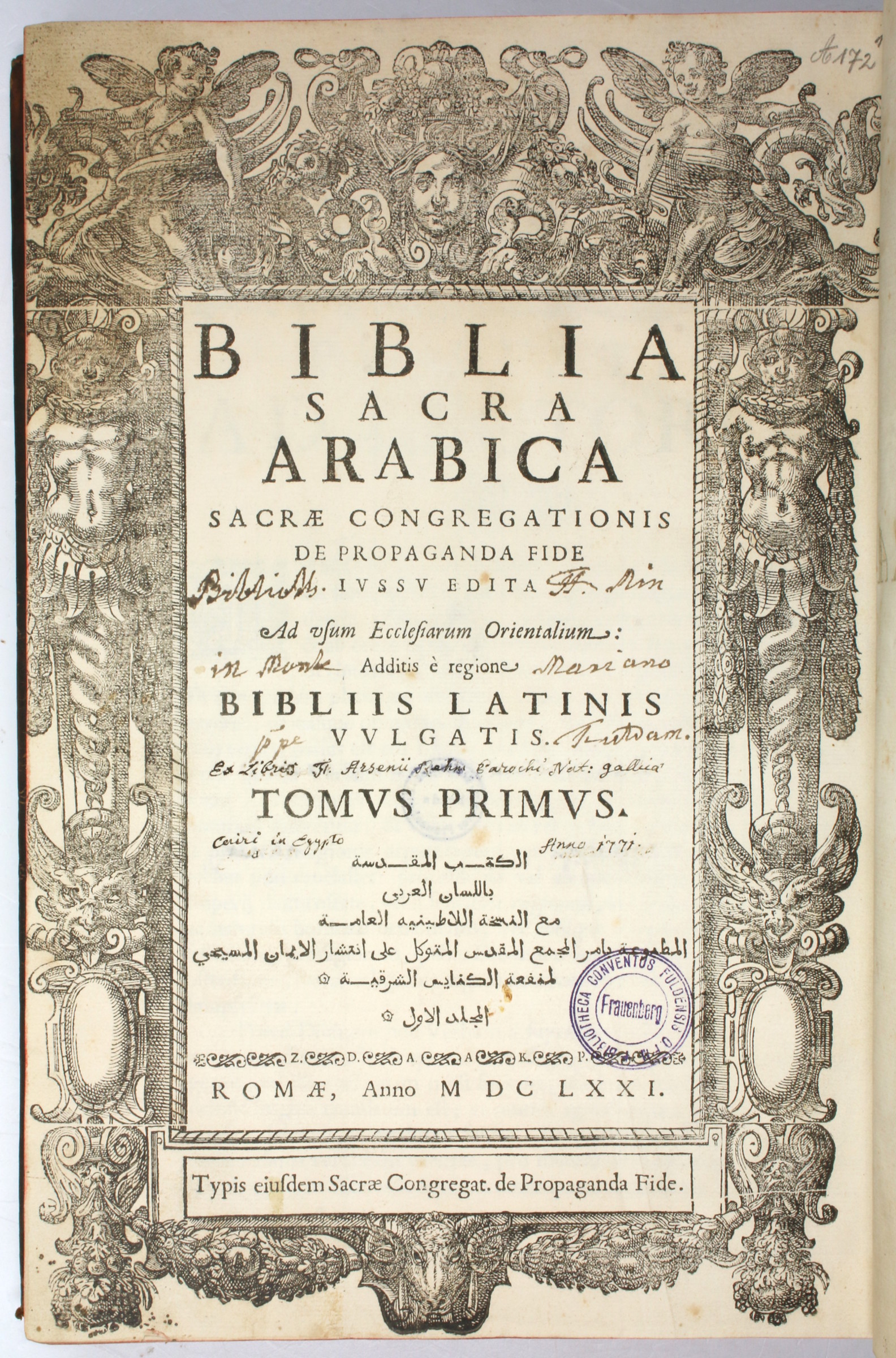

The so-called "Toledan Tables" are astronomical tables used to predict the movements of the Sun, Moon and planets relative to the fixed stars. They were completed around the year 1080 at Toledo by a group of Arab astronomers, led by the mathematician and astronomer Al-Zarqali (known to the Western World as Arzachel), and were first updated in the 1270s, afterwards to be referred to as the "Alfonsine Tables of Toledo". Named after their sponsor King Alfonso X, it "is not surprising that" these tables "originated in Castile because Christians in the 13th century had easiest access there to the Arabic scientific material that had reached its highest scientific level in Muslim Spain or al-Andalus in the 11th century" (Goldstein 2003, 1). The Toledan Tables were undoubtedly the most widely used astronomical tables in medieval Latin astronomy, but it was Giovanni Bianchini whose rigorous mathematical approach made them available in a form that could finally be used by early modern astronomy.

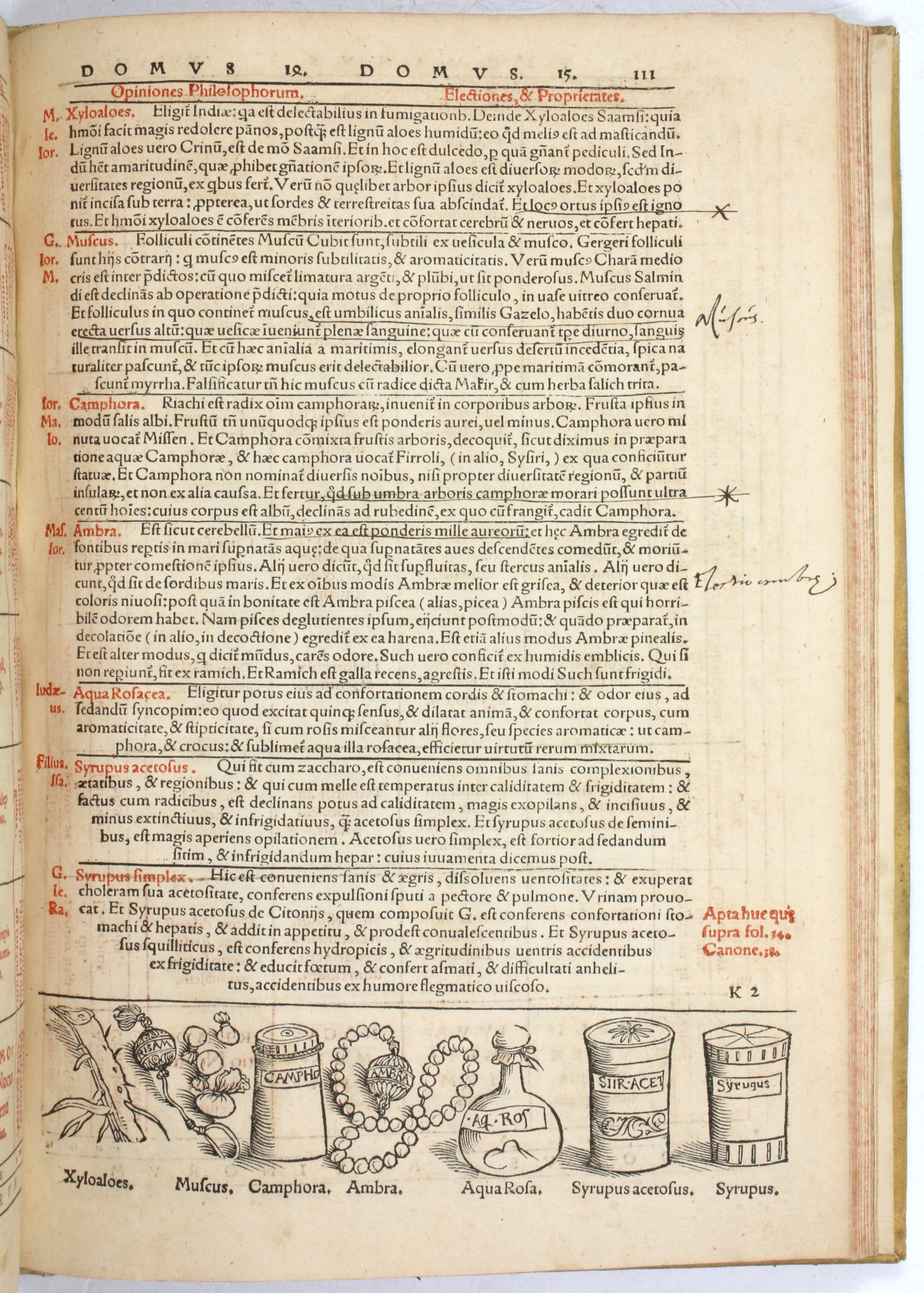

Bianchini was in fact "the first mathematician in the West to use purely decimal tables" and decimal fractions (Feingold, 20) by applying with precision the tenth-century discoveries of the Arab mathematician Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqilidisi, which had been further developed in the Islamic world through the writings of Al-Kashi and others (cf. Rashed, 88 and 128ff.). Despite the fact that they had been widely discussed and applied in the Arab world throughout a period of five centuries, decimal fractions had never been used in the West until Bianchini availed himself of them for his trigonometric tables in the "Tabulae de motis planetarum". It is this very work in which he set out to achieve a correction of the Alfonsine Tables by those of Ptolemy. "Thorndike observes that historically, many have erred by neglecting, because of their difficulty, the Alfonsine Tables for longitude and the Ptolemaic for finding the latitude of the planets. Accordingly, in his Tables Bianchini has combined the conclusions, roots and movements of the planets by longitude of the Alfonsine Tables with the Ptolemaic for latitude" (Tomash, 141).

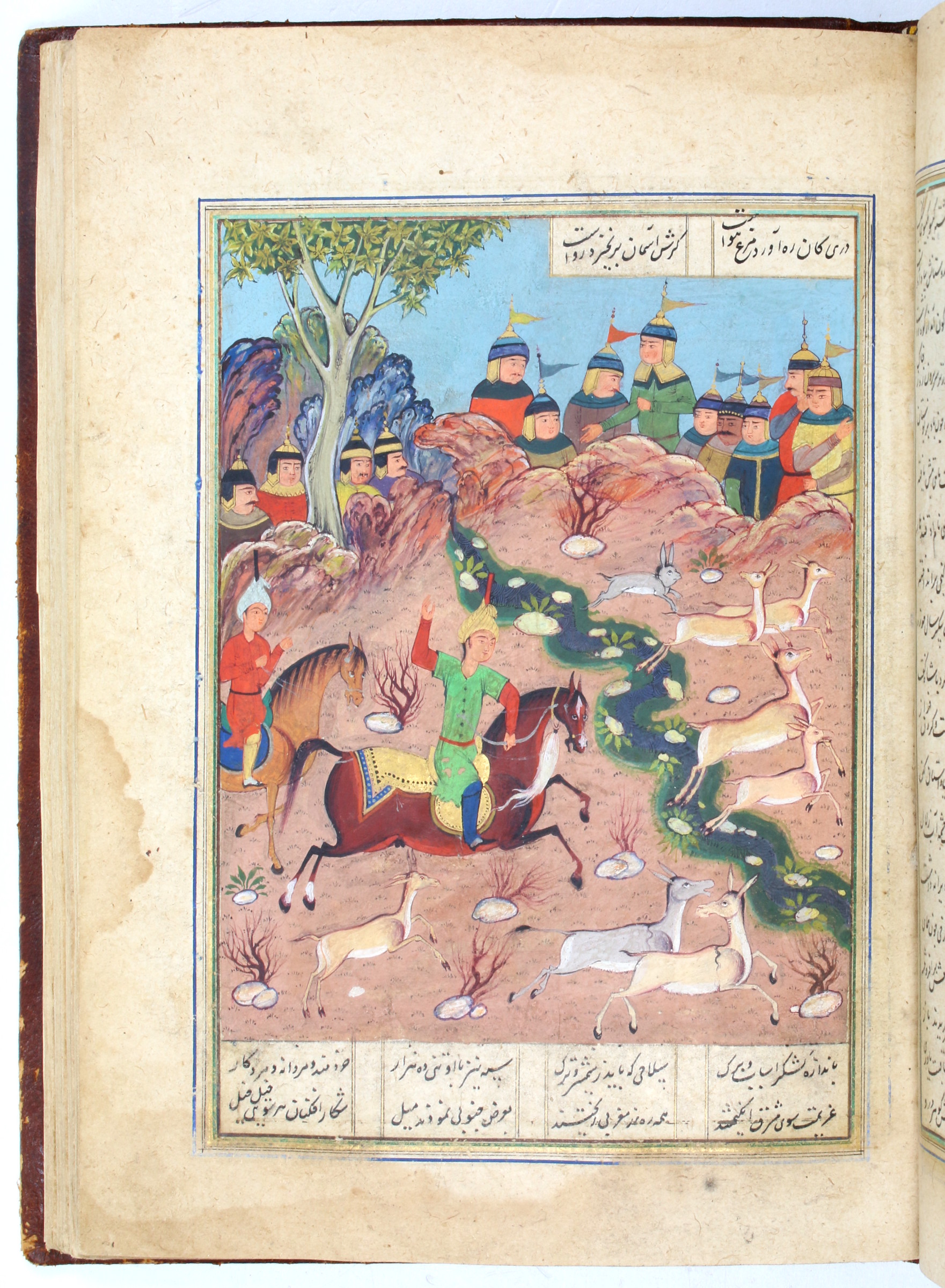

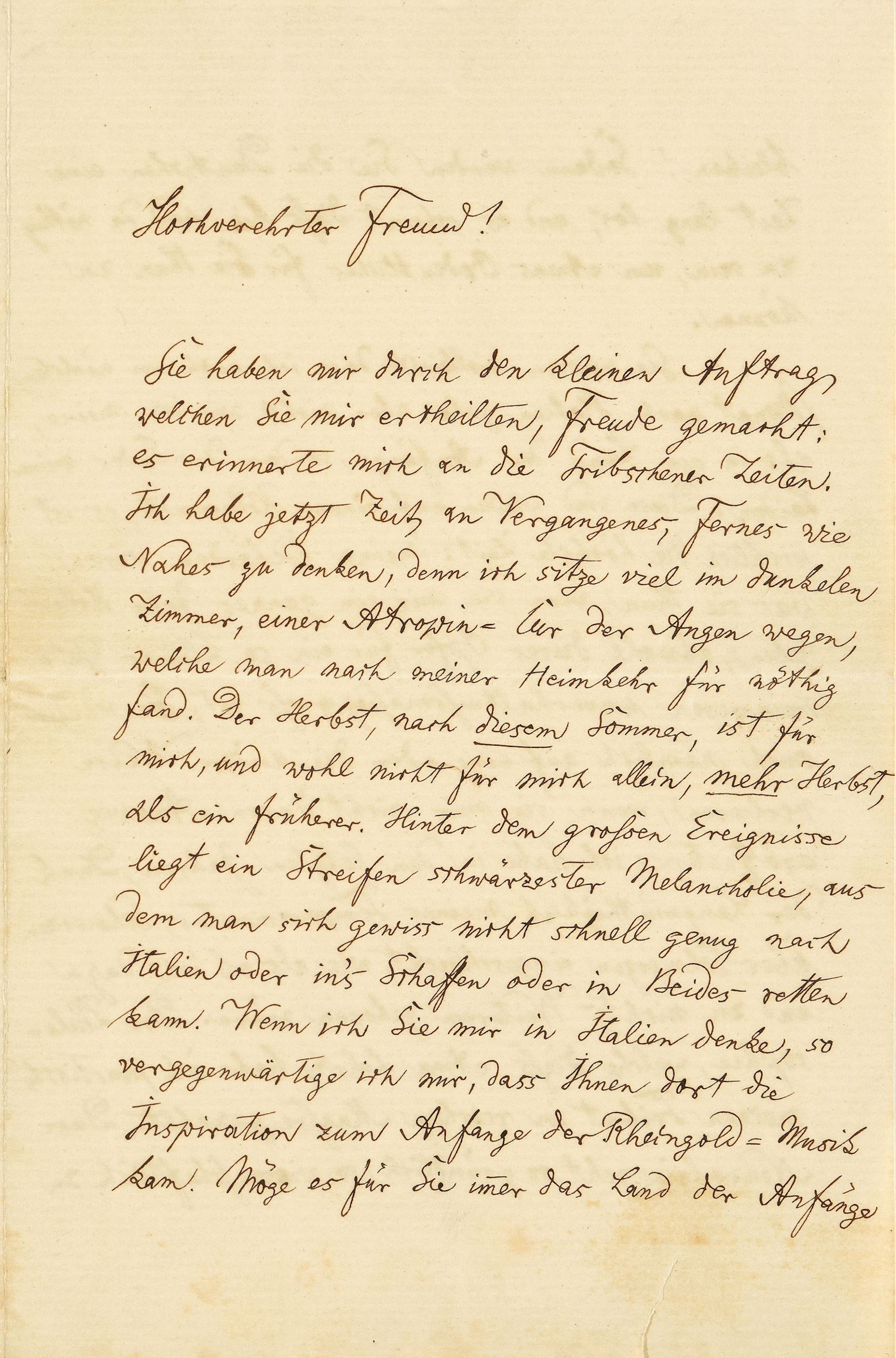

The importance of the present work, today regarded as representative of the scientific revolutions in practical mathematics and astronomy on the eve of the Age of Discovery, is underlined by the fact that it was not merely dedicated but also physically presented by the author to the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in person on the occasion of Frederick's visit to Ferrara. In return for his "Tabulae", a "book of practical astronomy, containing numbers representing predicted times and positions to be used by the emperor's […] astrologers in managing the future" (Westman, 10ff.), Bianchini was granted a title of nobility by the sovereign.

For Regiomontanus, who studied under Bianchini together with Peurbach, the author of the "Tabulae" counted as the greatest astronomer of all time, and to this day Bianchini's work is considered "the largest set of astronomical tables produced in the West before modern times" (Chabbas 2009, VIII). Even Copernicus, a century later, still depended on the "Tabulae" for planetary latitude (cf. Goldstein 2003, 573), which led to Al-Zarquali's Tables - transmitted in Bianchini's adaption - ultimately playing a part in one of the greatest revolutions in the history of science: the 16th century shift from geocentrism to the heliocentric model.

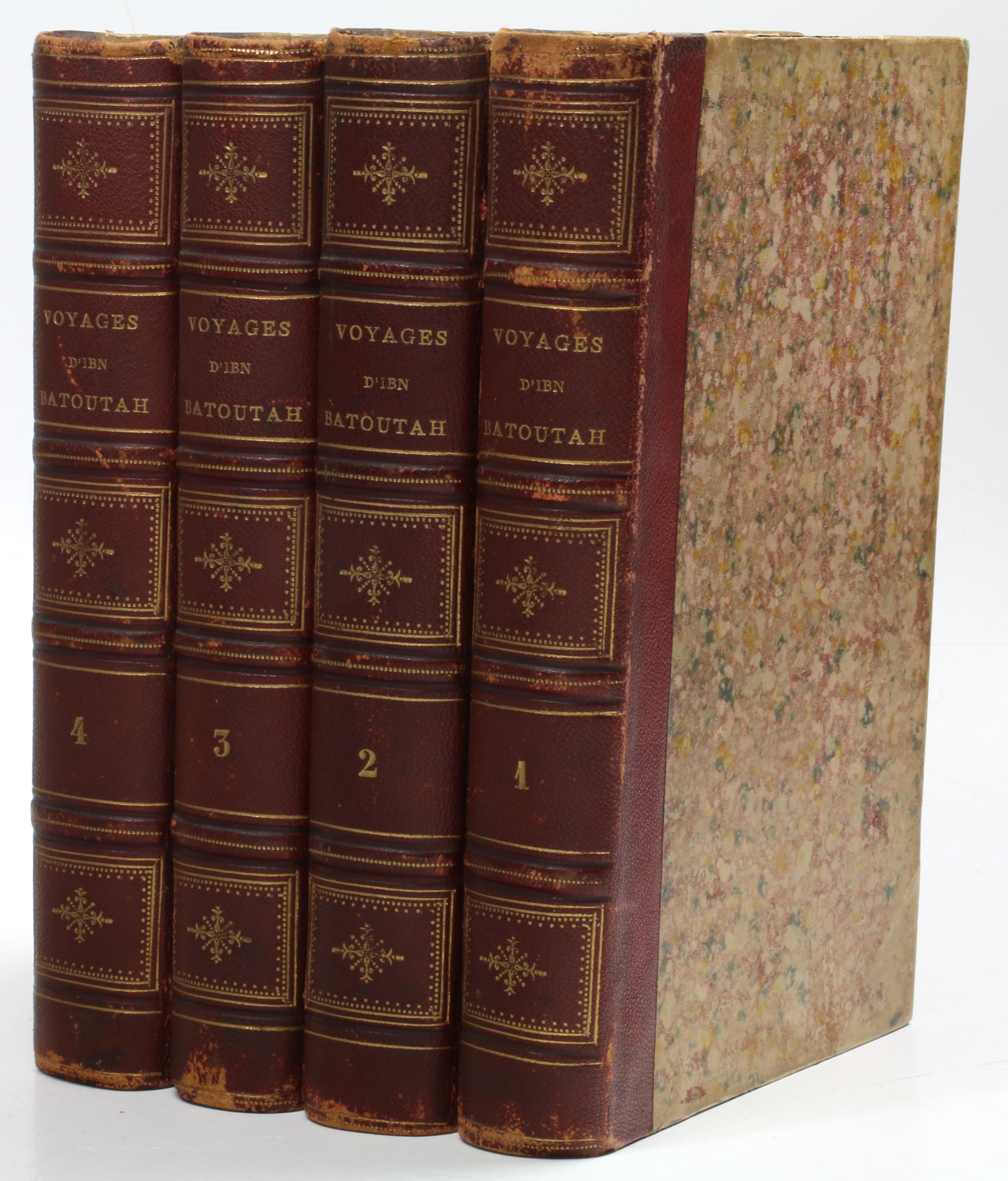

In the year 1495, some 20 years after our manuscript was written, Bianchini's Tables were printed for the first time, followed by editions in 1526 and 1563. Apart from these printed versions, quite a few manuscript copies of his work are known in western libraries - often comprising only the 231 full-page Tables but omitting the 68-page introductory matter explaining how they were calculated and meant to be used, which is present in our manuscript. Among the known manuscripts in public collections is one copied by Regiomontanus, and another written entirely in Copernicus's hand (underlining the significance of the Tables for the scientific revolution indicated above), but surprisingly not one has survived outside Europe. Indeed, the only U.S. copy recorded by Faye (cf. below) was the present manuscript, then in the collection of Robert Honeyman. There was not then, nor is there now, any copy of this manuscript in an American institution. Together with one other specimen in the Erwin Tomash Library, our manuscript is the only preserved manuscript witness for this "crucial text in the history of science" (Goldstein 2003, publisher's blurb) in private hands. Apart from these two examples, no manuscript version of Bianchini's "Tabulae" has ever shown up in the trade or at auctions (according to a census based on all accessible sources).

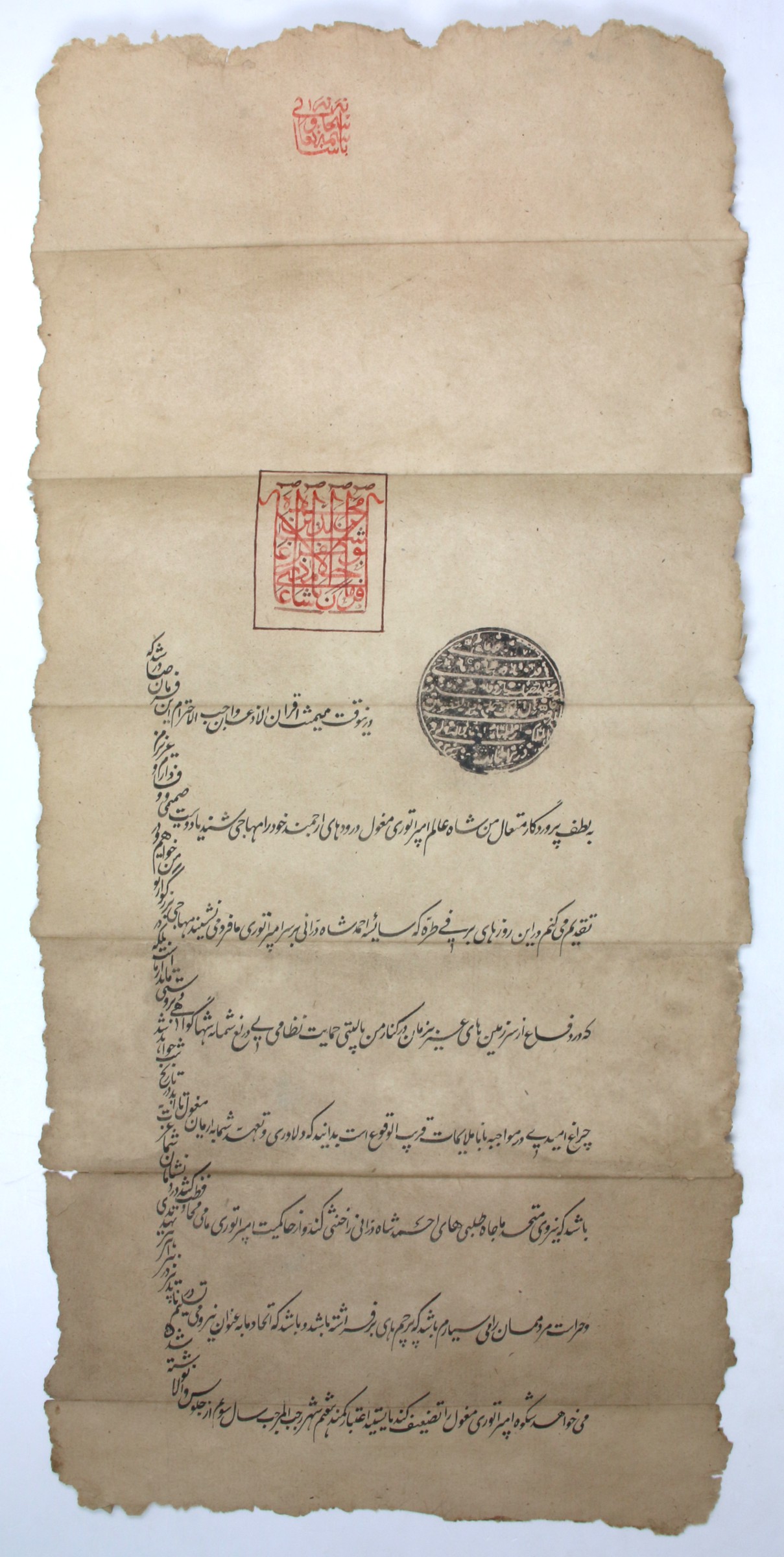

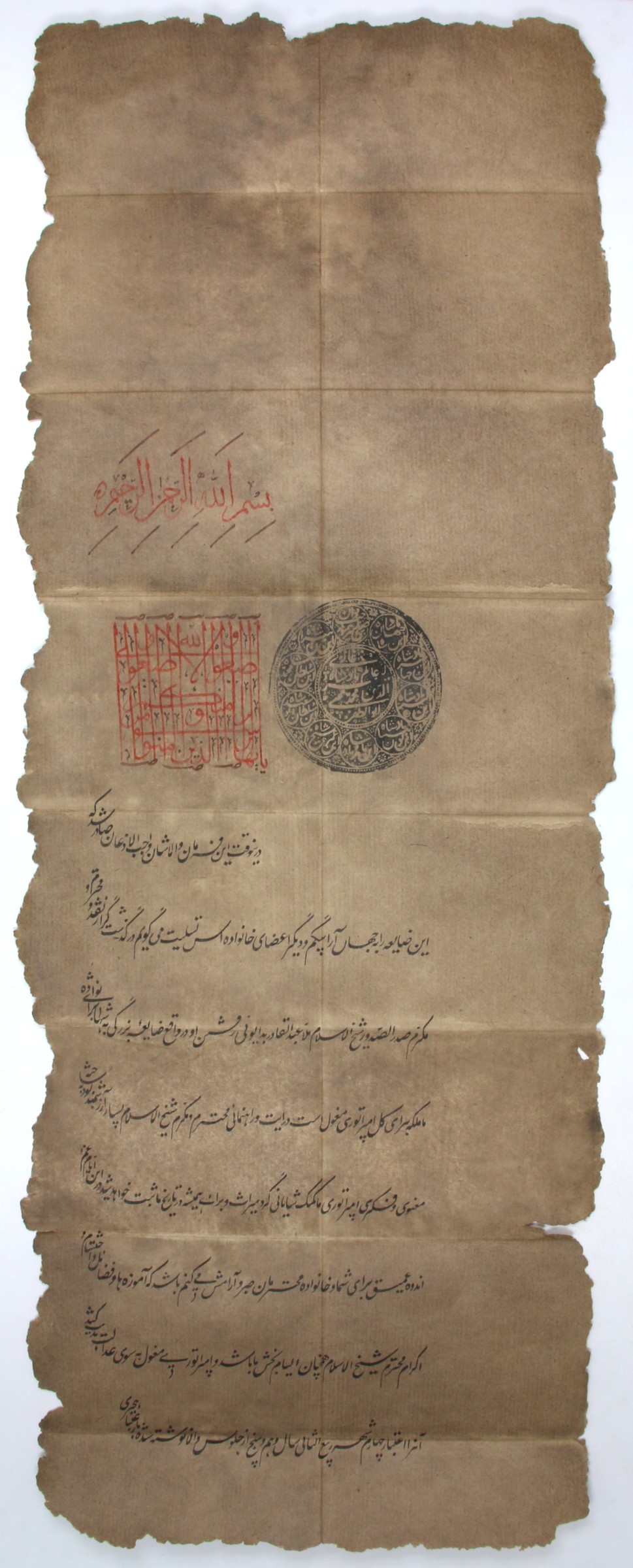

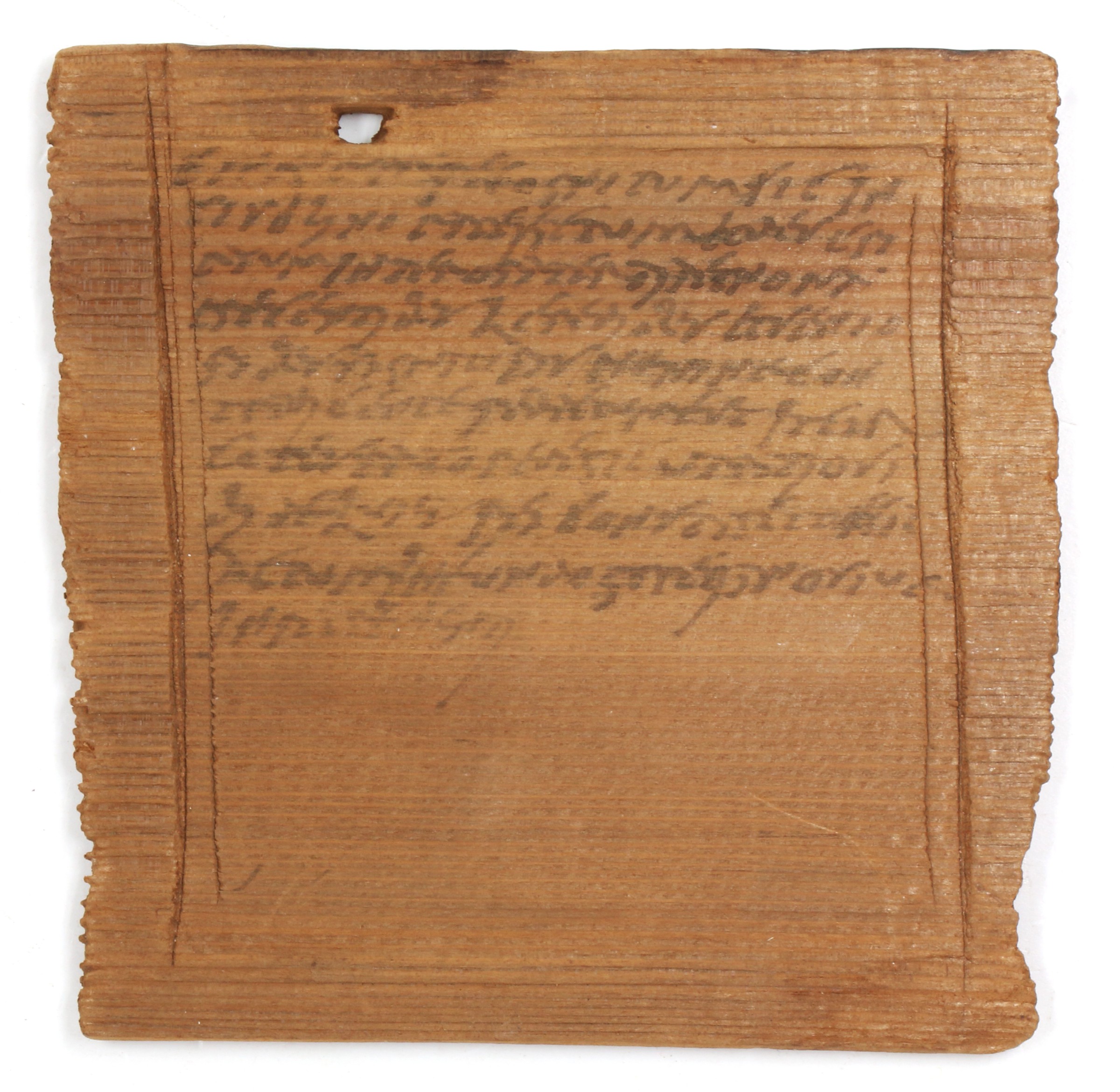

Condition: watermarks identifiable as Briquet 3387 (ecclesiastical hat, attested in Florence 1465) and 2667 (Basilisk, attested to Ferrara and Mantua 1447/1450). Early manuscript astronomical table for the year 1490 mounted onto lower pastedown. Minor waterstaining in initial leaves and a little worming at back, but generally clean and in a fine state of preservation. Italian binding sympathetically rebacked, edges of covers worn to wooden boards. A precious manuscript, complete and well preserved in its original, first binding.

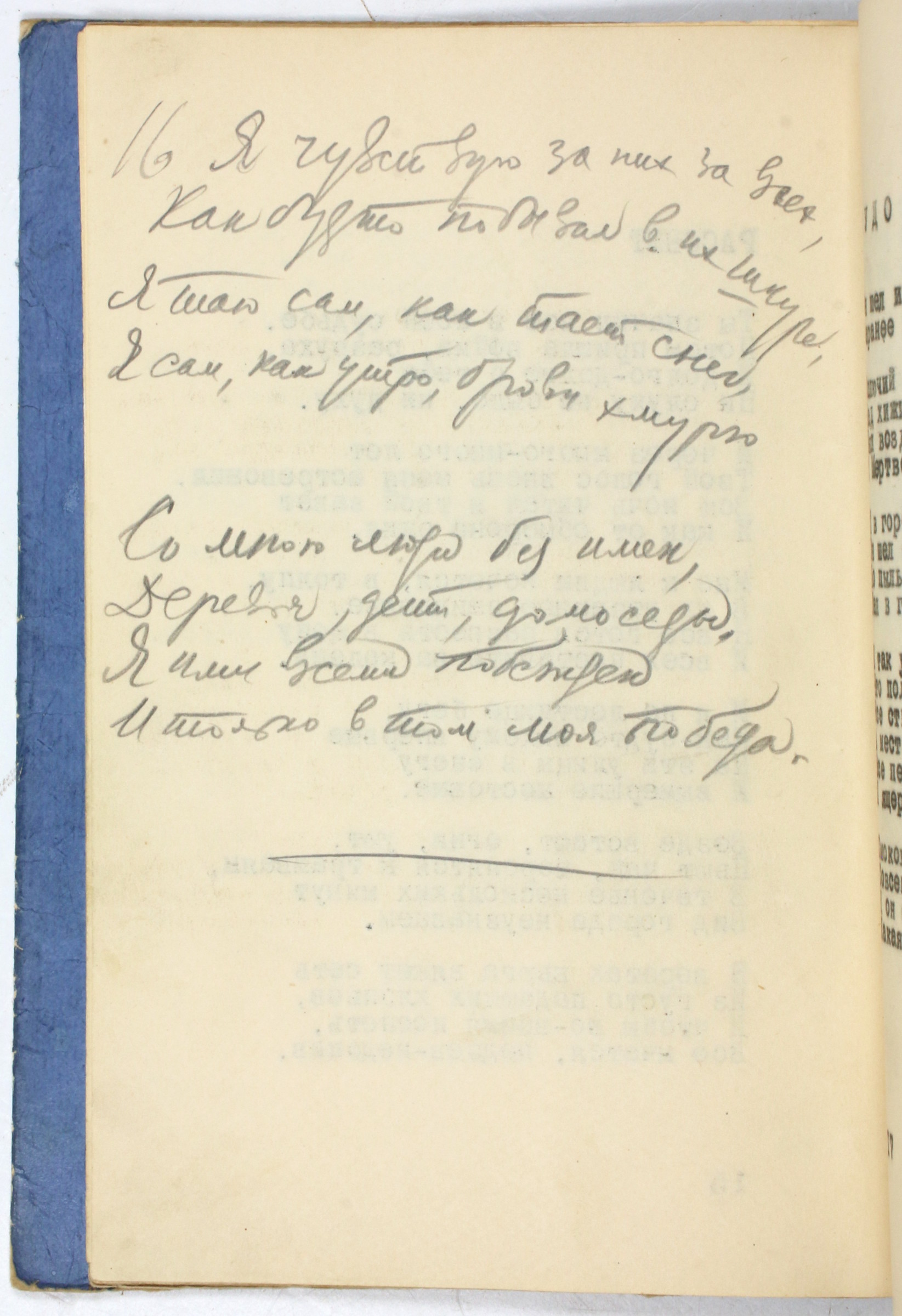

Provenance: 1) Written ca 1475 by Francesco da Quattro Castella (his entry on fol. 150v) for 2) Marco Antonio Scalamonte from the patrician family of Ancona, who became a senator in Rome in 1502 (his illuminated coat of arms on fol. 1r). 3) Later in an as yet unidentified 19th century collection of apparently considerable size (circular paper label on spine "S. III. NN. Blanchinus. MS.XV. fol. 43150"). 4) Robert Honeyman, Jr. (1928-1987), probably the most prominent U.S. collector of scientific books and manuscripts in the 20th century, who "had a particular interest in astronomy" (S. Horobin, 238), his shelf mark "Astronomy MS 1" on front pastedown. 5) Honeyman Collection of Scientific Books and Manuscripts, Part III, Sotheby's, London, Wed May 2, 1979, lot 1110, sold to 6) Alan Thomas (1911-1992), his catalogue 43.2 (1981), sold to 7) Hans Peter Kraus (1907-1988), sold to 8) UK private collection.